Red Summer

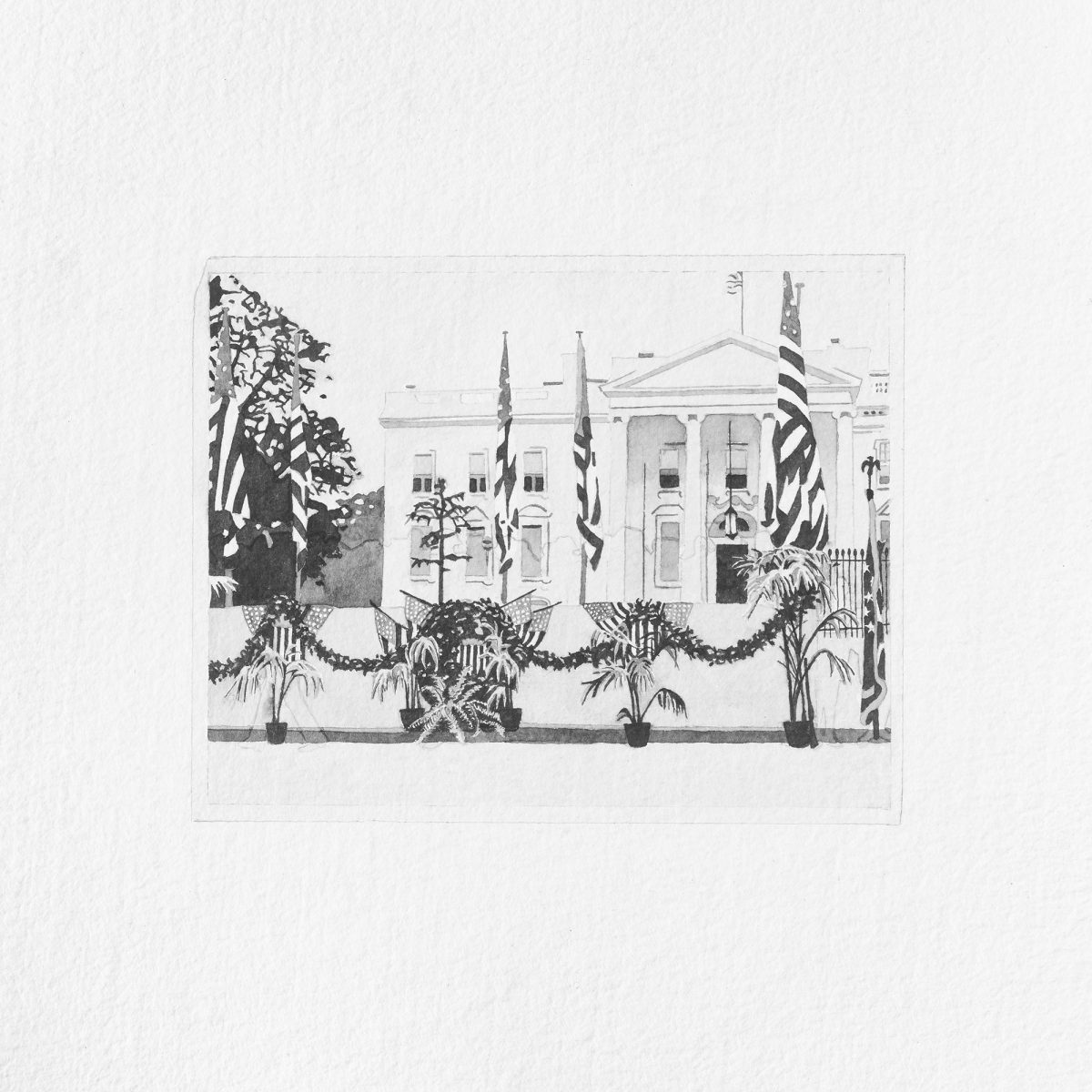

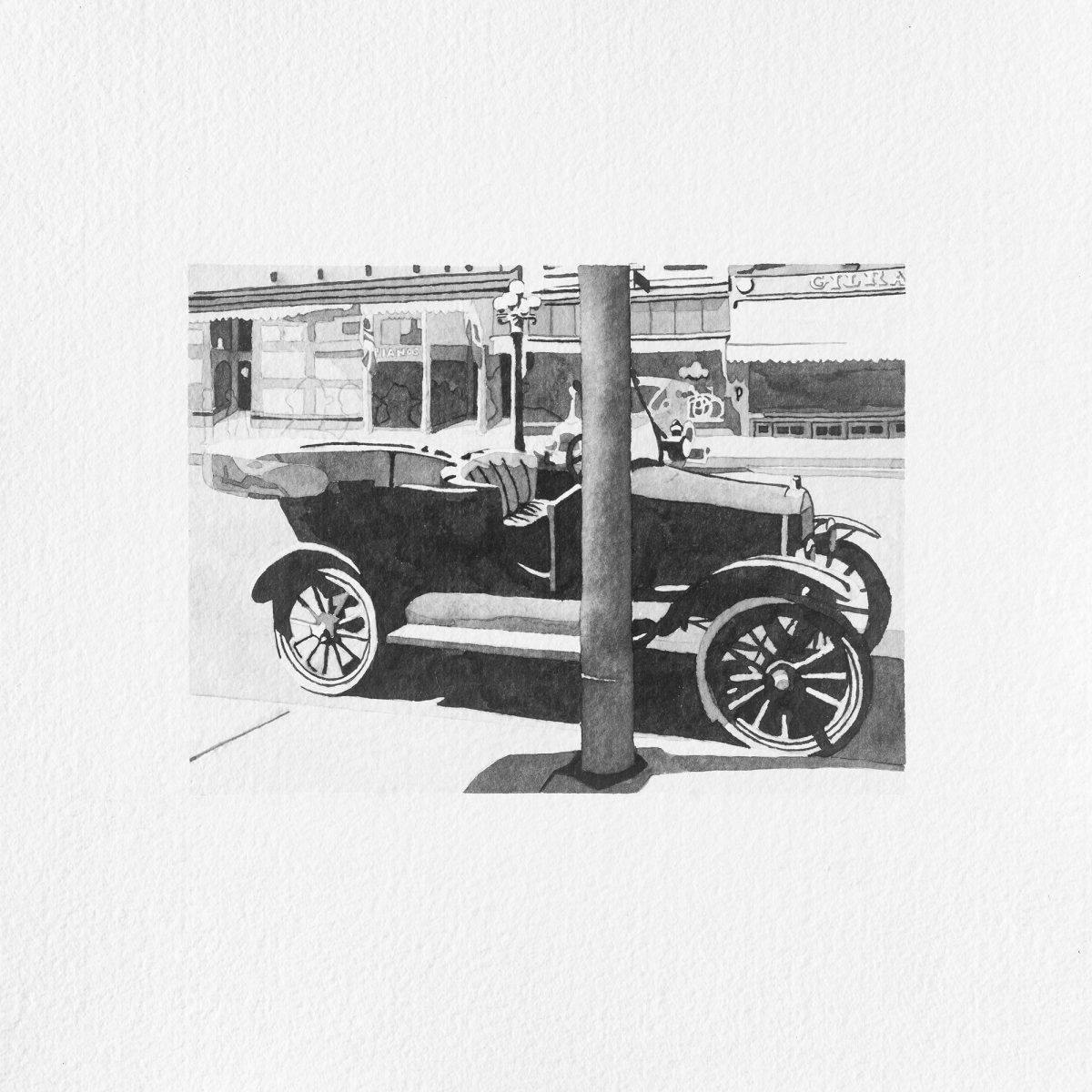

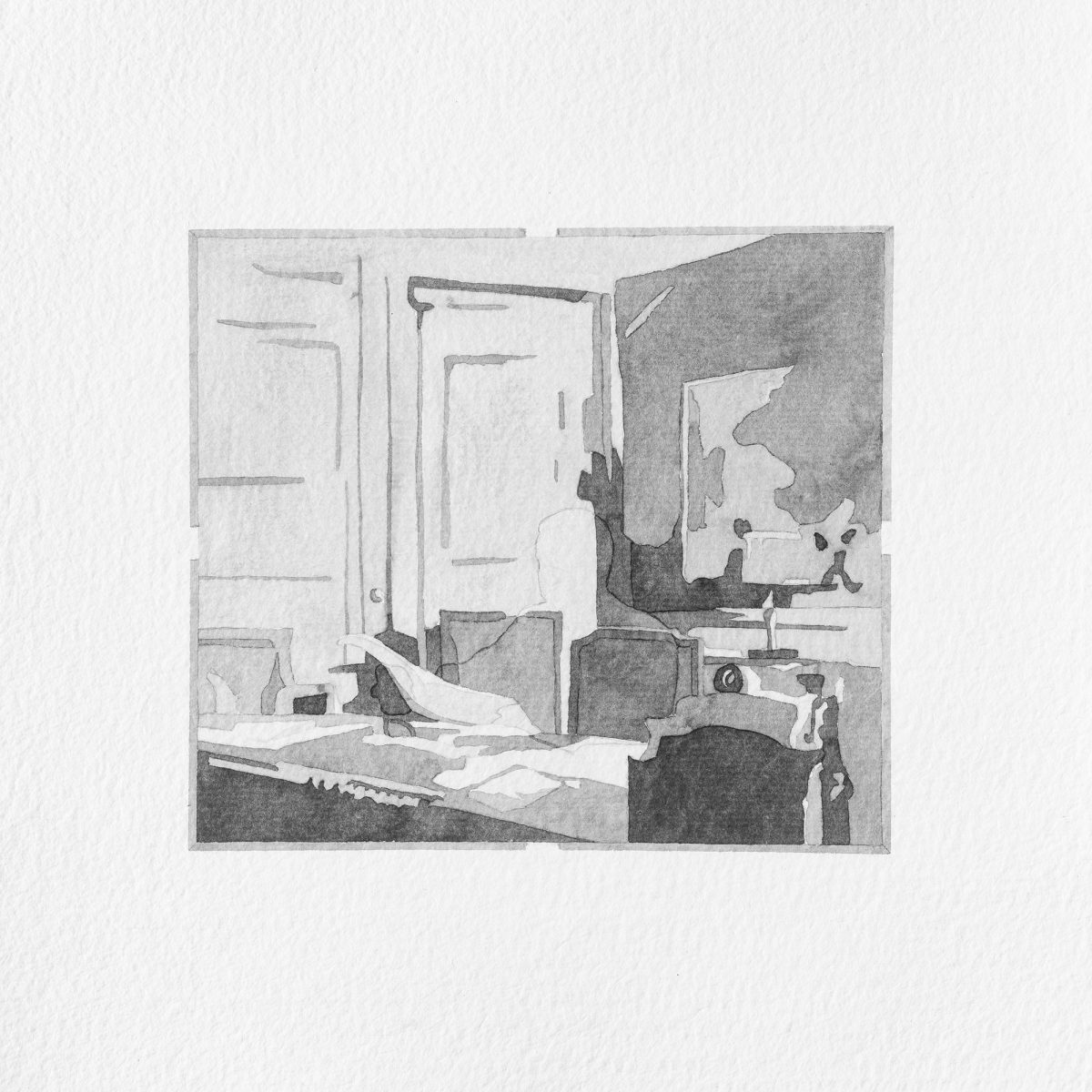

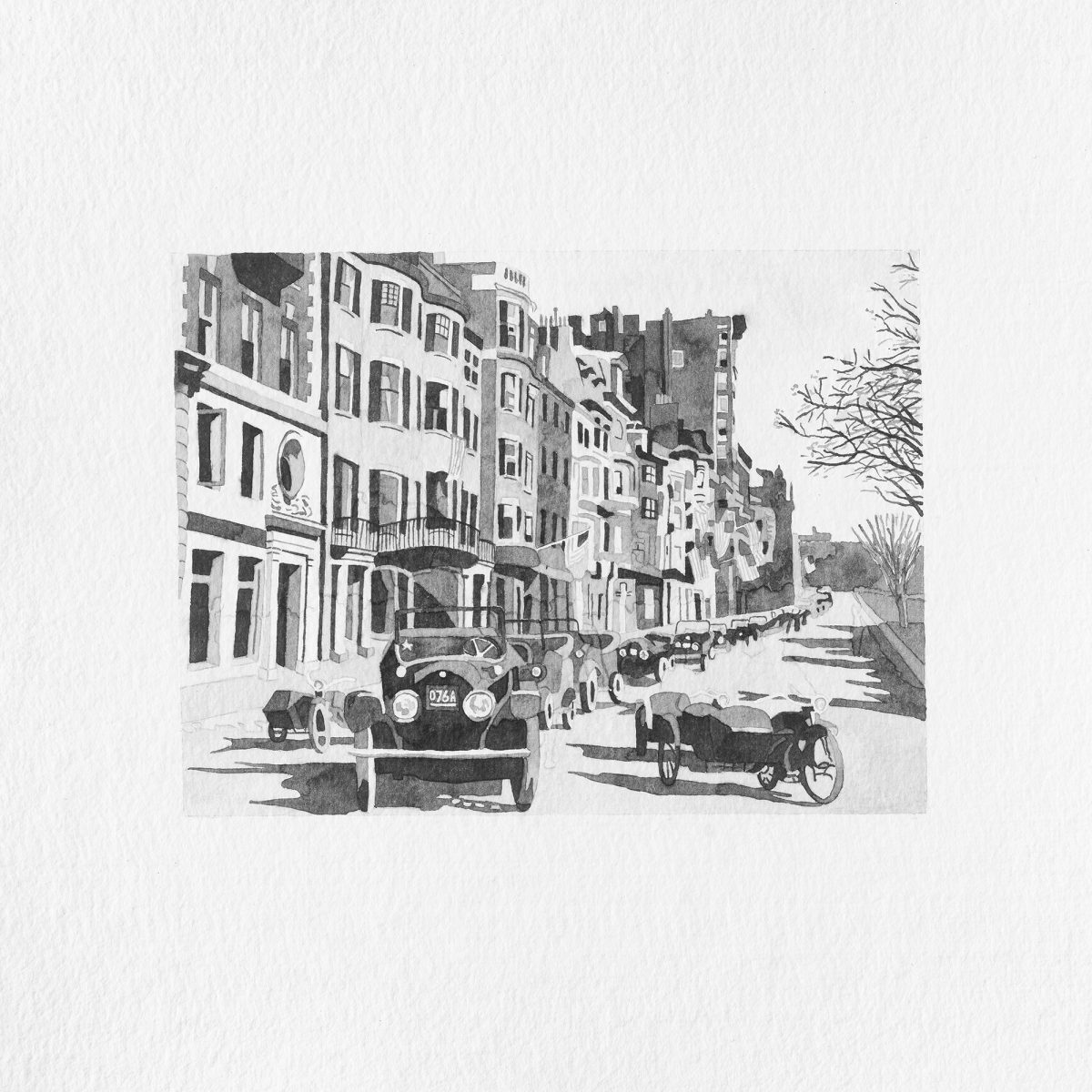

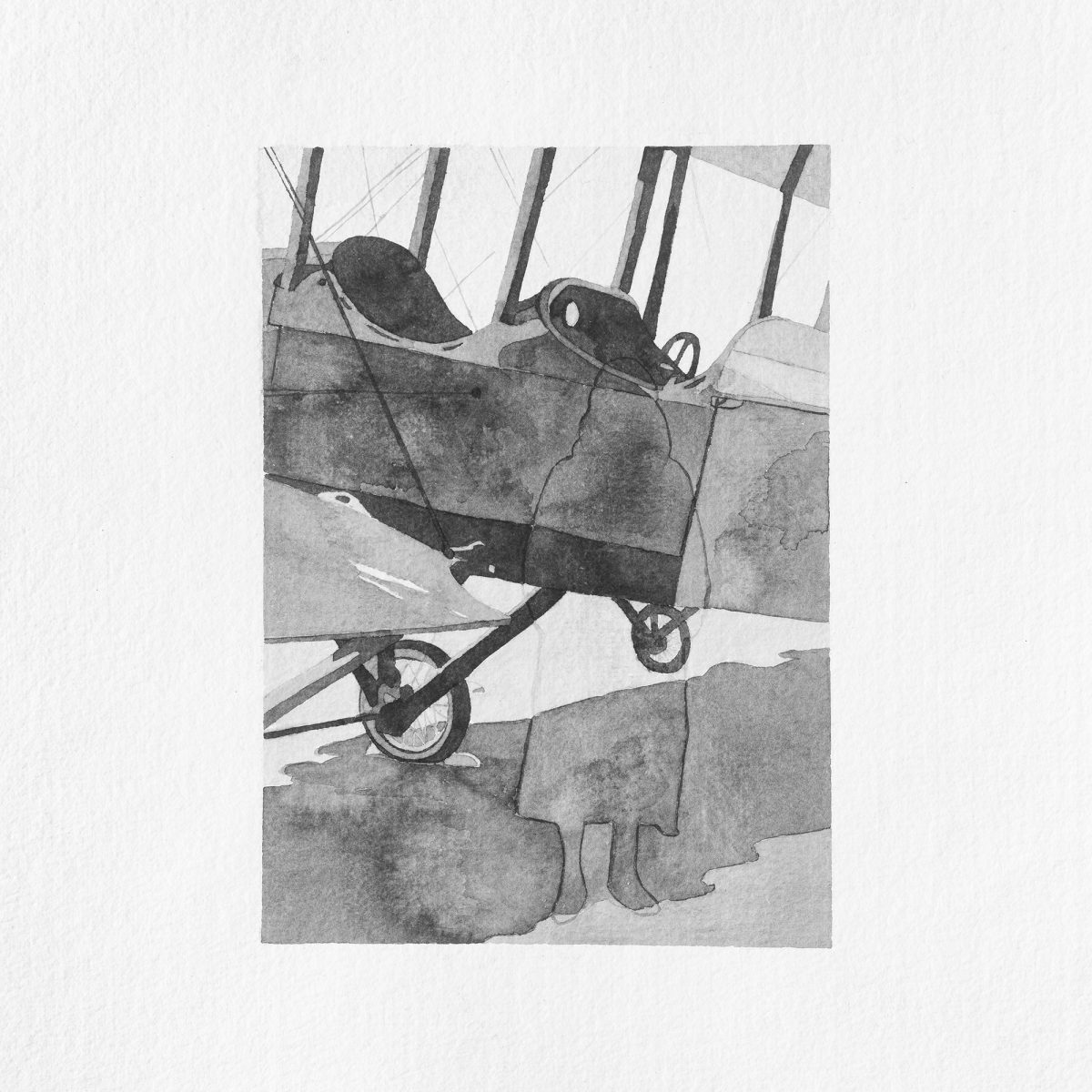

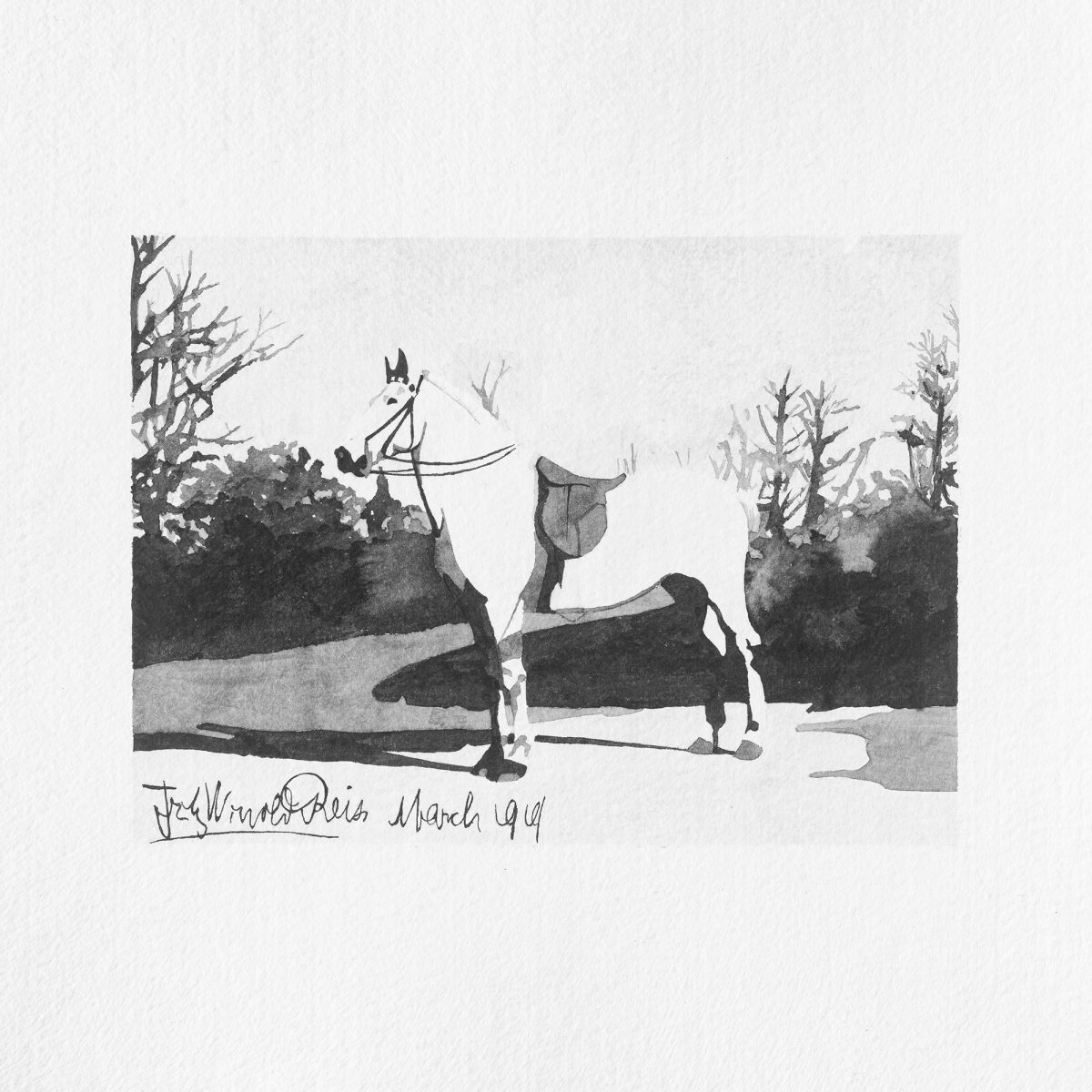

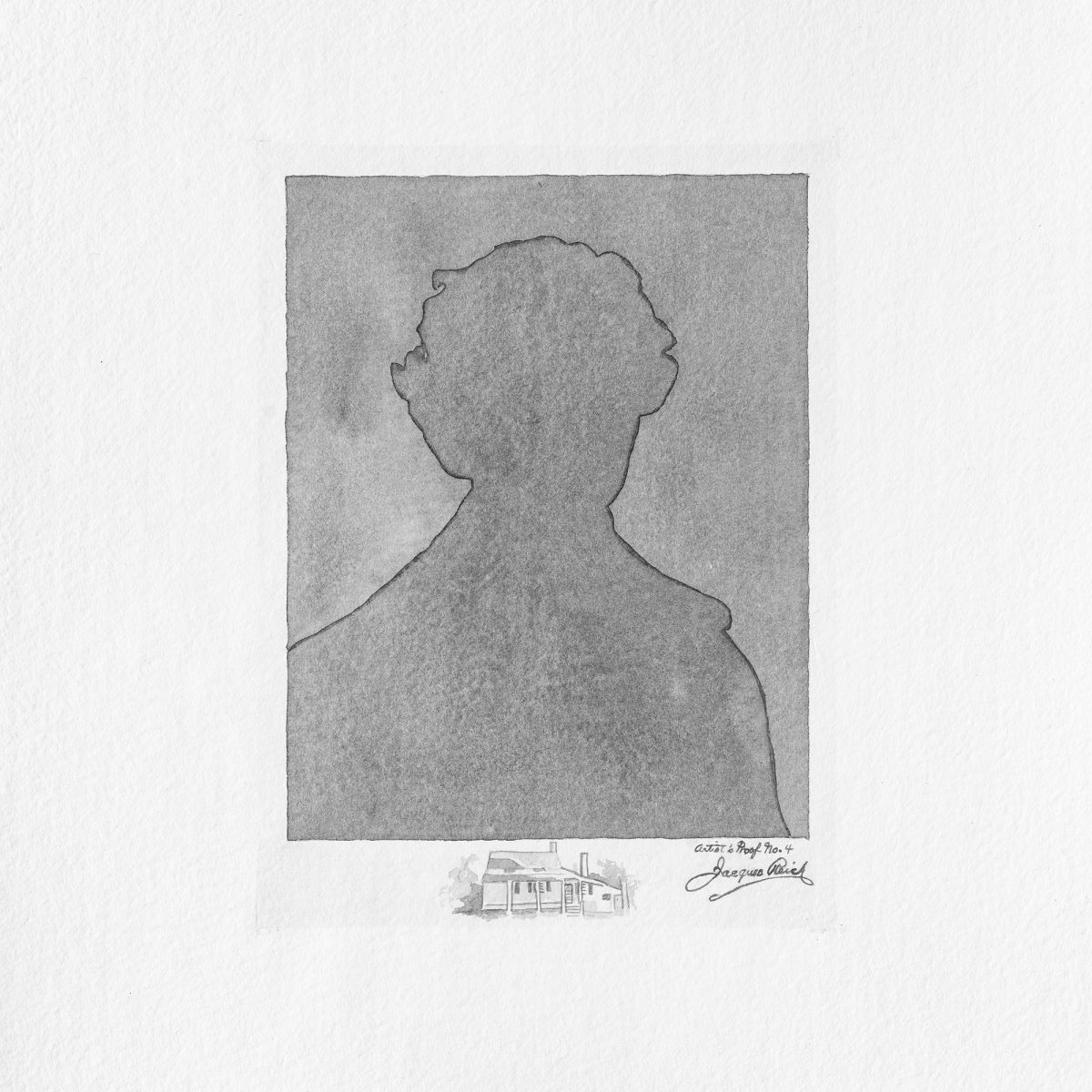

Completed as part of a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, Red Summer: A Look At, and Away From, America’s Deadliest Year of Interracial Violence Through a Re-rendering of Forty-Seven Objects From That Year in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (2016–19) looks at the bloody year of 1919.

1919 marked the deadliest period of white-on-black violence in U.S. history, with over twenty-five race riots—most started by white mobs—breaking out across the nation. The bloodshed led civil-rights activist James Weldon Johnson to dub the period the “Red Summer.” 1919 was also when the Smithsonian Institution began planning its National Portrait Gallery, whose mission has been to “acquire and display portraits of men and women who have made significant contributions to the history, development, and culture of the people of the United States.” Yet all of the subjects in the museum’s works from 1919 are white, and the few with any connection to the racial tensions of the time came down on the wrong side of that history.

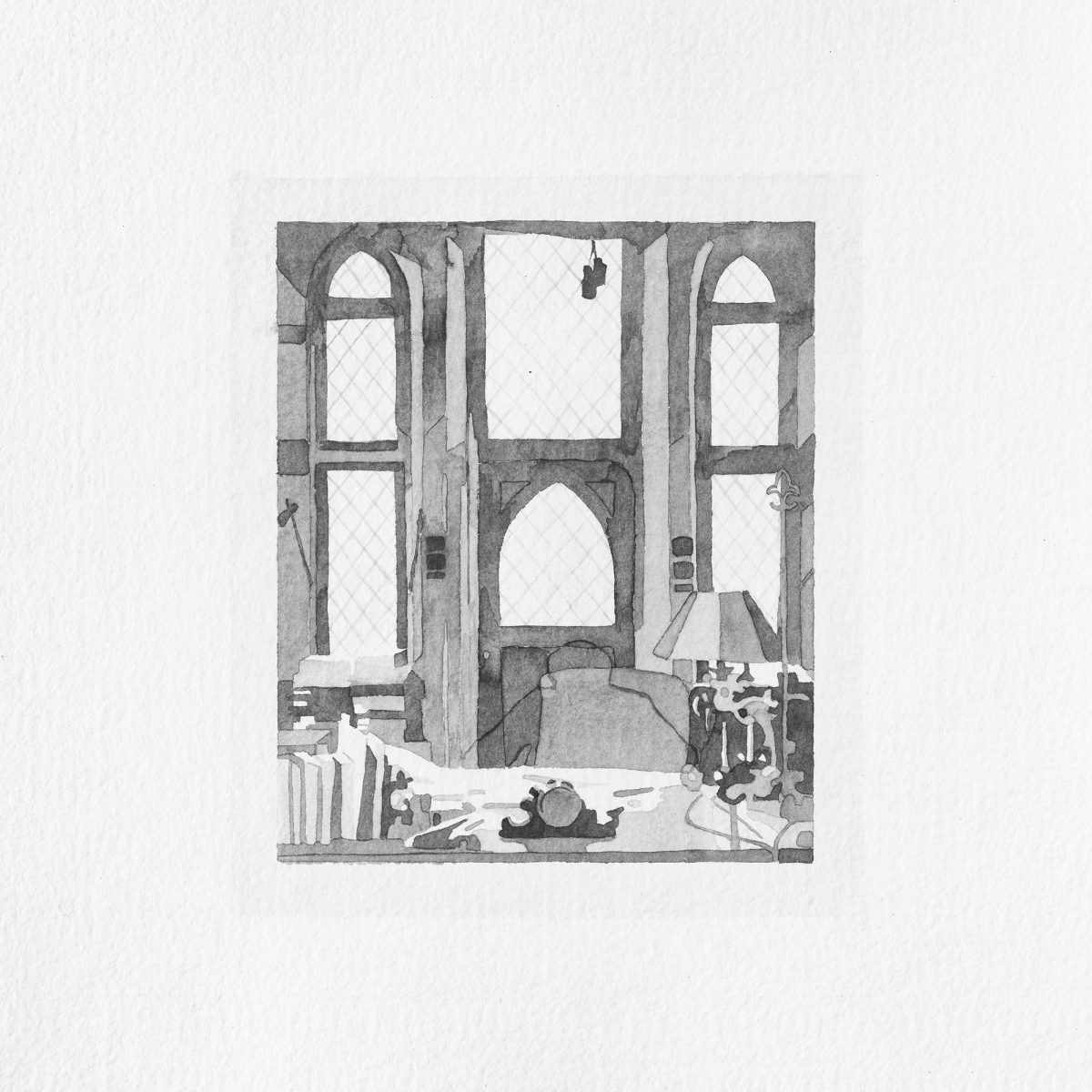

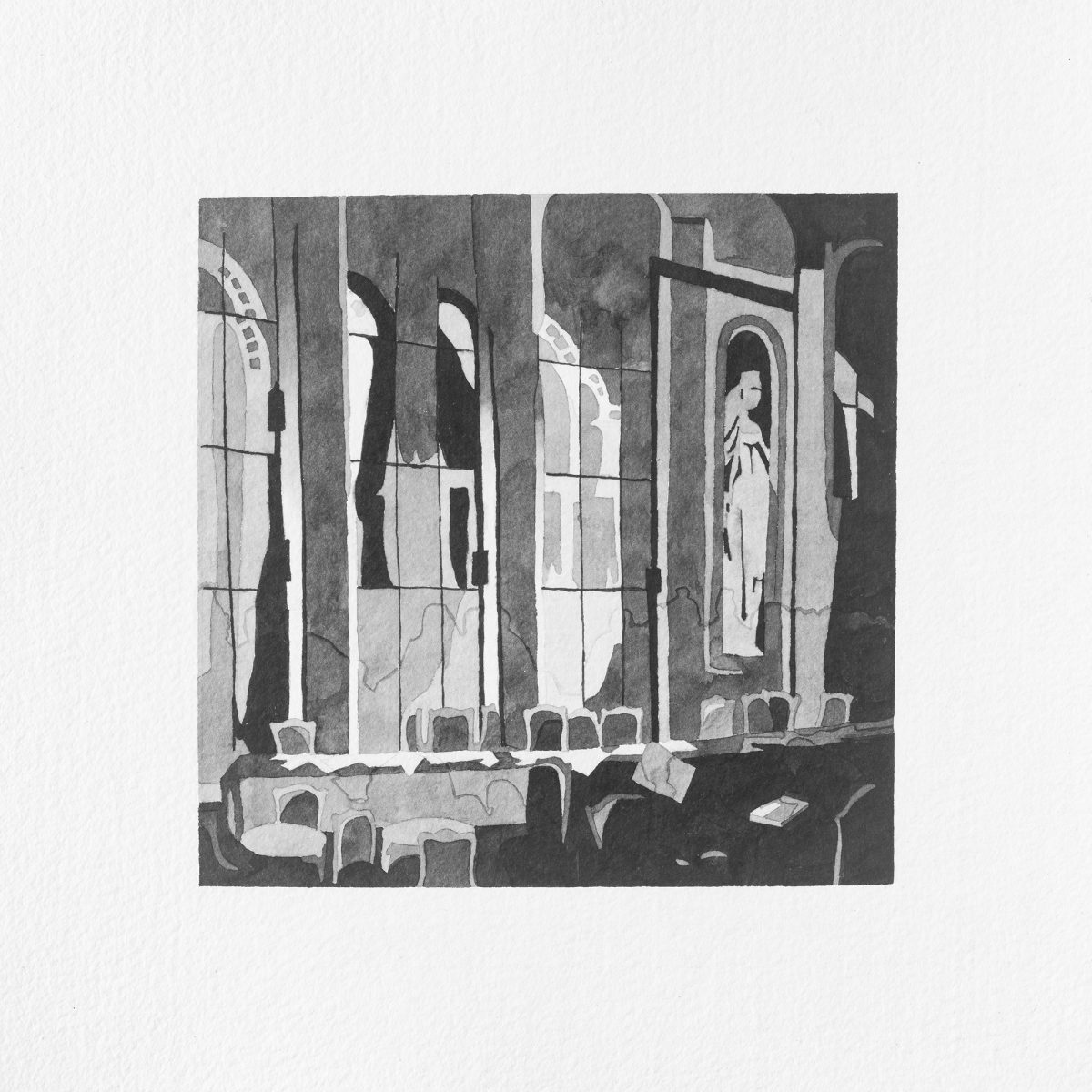

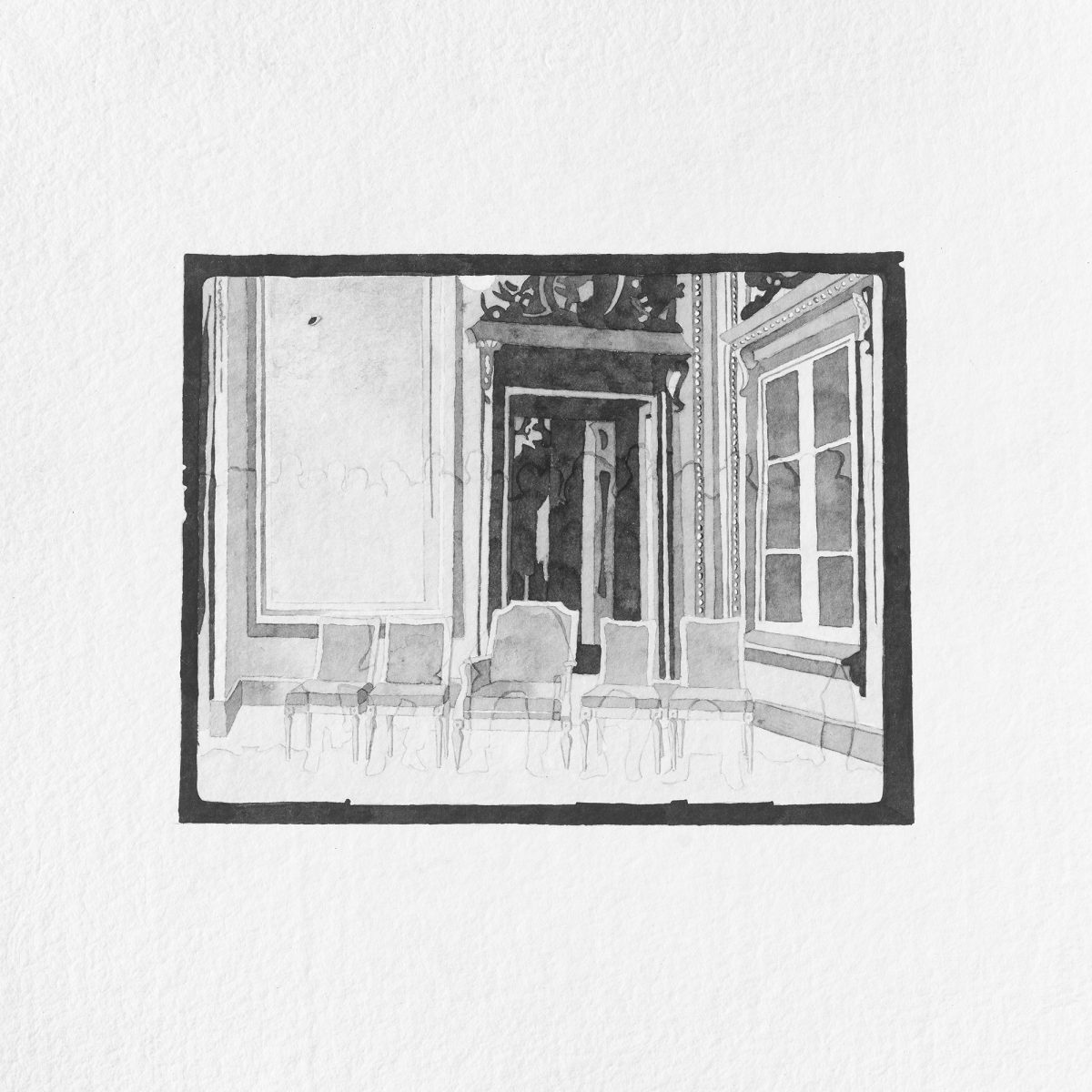

Functioning as a kind of anti-portraiture, Red Summer re-renders, in ink on paper, the forty-seven paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection from the year 1919, but with the sitter of the portrait redacted, leaving only a ghostly outline. An image of Woodrow Wilson attending a ceremony outside the White House thus becomes a vacant sidewalk festooned in American flags; a painting of General Pershing witnessing the signing of the treaty that ended World War I becomes an empty Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles. These intentional erasures work to reorient our gaze away from the individuals who have been canonized as important historical figures and turn it toward the space surrounding them, thereby challenging the dominant narrative of our country’s past and implicitly asking: Whom have we been missing?